Your 3PL sends a clean monthly invoice. Storage fees. Pick and pack charges. Shipping costs. Everything looks predictable.

But that invoice rarely shows what you are actually paying.

Most DTC brands choose fulfillment based on visible costs: warehouse location, per-unit fees, storage rates. These matter, but they miss the operational dynamics that shape your overall cost structure.

If you manufacture in Asia and sell in North America, the traditional model forces you to optimize for the wrong variables. These variables made sense when ocean freight and domestic warehousing were the only options.

Today, they introduce hidden costs that compound as you grow.

On paper, you see three clean numbers: storage per cubic foot, pick and pack fees, and domestic shipping rates. These give the illusion that you can model your unit economics simply by plugging numbers into a spreadsheet.

The real costs live elsewhere.

Zone premiums grow as your customer base spreads across the country. Capital stays locked for sixty to ninety days before a single order ships. Quality issues are discovered weeks after production, when your inventory is already thousands of miles away from the factory. Every new product test requires container scale, which forces you into decisions that are expensive to reverse.

These costs never appear on your invoice because they are created by the structure of your supply chain, not by the warehouse itself. Brands that scale efficiently understand that it is the second group, not the line items, that determines margin and cash flow.

What appears on invoices:

What never appears:

Brands that scale efficiently optimize for the second group, not the first.

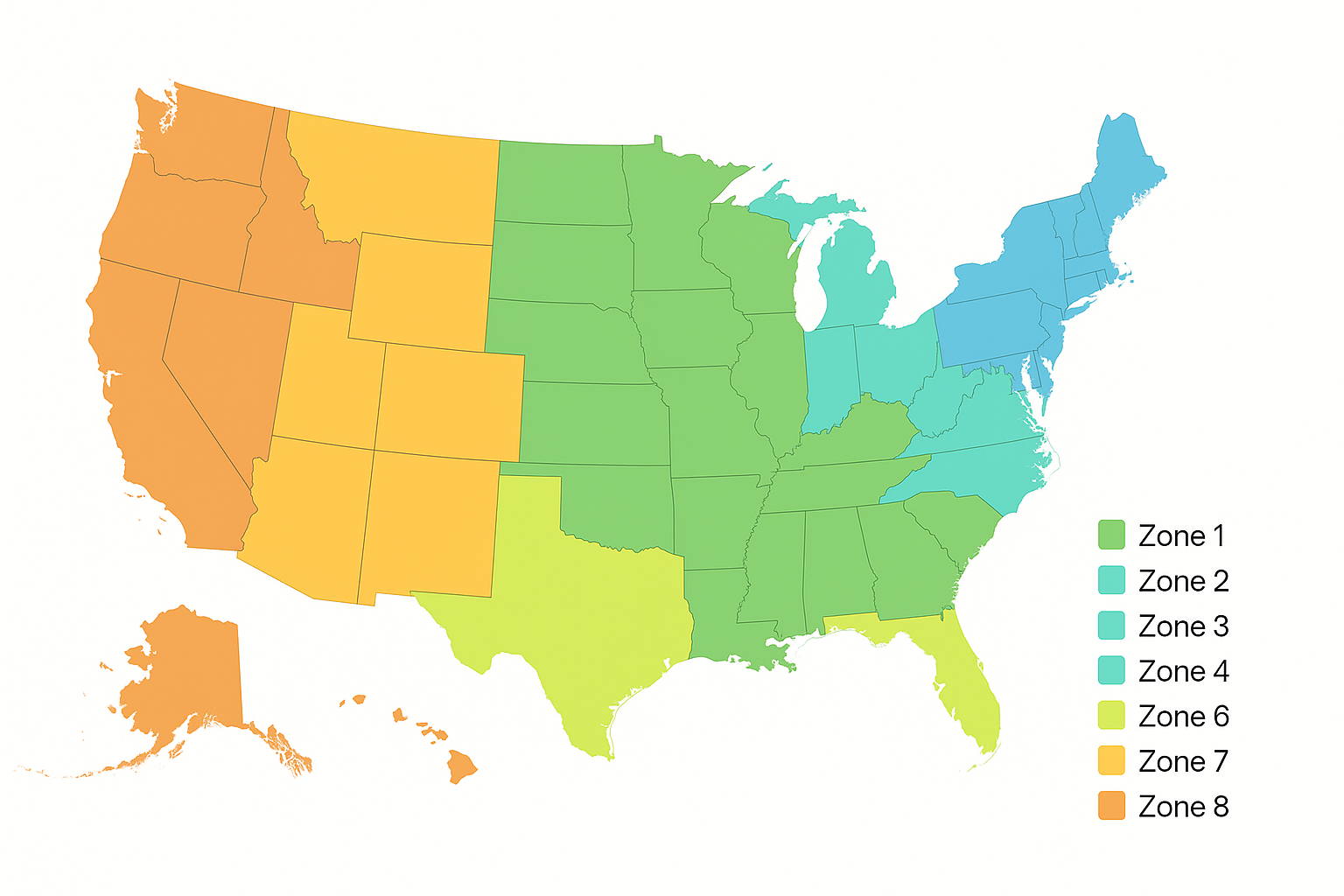

Carriers price by zones. The farther a package travels from your warehouse, the more you pay.

When you 3PL sits on the west coast, every east coast customer becomes a far zone delivery.

A two-pound US Priority Mail package:

That is 52% more expensive for far-zone deliveries.

If your 3PL sits in Kentucky, every California customer pays that premium. Many brands try to solve this by splitting inventory across several warehouses, but this creates new problems.

For a brand shipping ten thousand orders per month with 40% landing in far zones, the annual zone premium alone can exceed twenty thousand dollars.

Direct fulfillment solves this differently. Packages enter North American carrier networks after customs, which means they are not anchored to a single warehouse. With a multi-carrier network, shipments to Miami and Vancouver can use entirely different routes, even when they clear customs on the same day.

Carrier choice becomes the optimization layer, not warehouse geography.

The cash conversion cycle tracks how long your capital sits idle between paying suppliers and receiving cash from customers.

Day 1: Pay supplier

Day 45-60: Ocean freight

Day 65: Arrives at domestic 3PL

Day 70: First sales

Day 79: Cash received

Total time: 79 days

Day 1: Pay supplier

Day 3: Arrives at factory-adjacent center

Day 5: First sales

Day 12: Orders delivered

Day 26: Cash received

Total time: 26 days

That is a 53-day improvement.

With $200,000 in working capital:

Faster cycles free cash, improve planning accuracy, and allow brands to respond to real demand signals rather than three-month-old forecasts.

Use our Direct Fulfillment ROI Calculator to model your own cash cycle improvement.

You produce 5,000 units in Guangdong. Six weeks later, your 3PL discovers defects during receiving.

Every option hurts:

Factory-adjacent fulfillment compresses the discovery window.

Products arrive within hours. Inspection happens immediately. Defective units can be returned to the factory the same day and corrected the next day.

Traditional cost: at least five thousand dollars or a likely write-off

Factory-adjacent cost: local transport plus repair

This is the 1-10-100 rule applied to supply chains. Fixing issues at the source costs one dollar. Fixing issues during fulfillment costs ten. Fixing issues after delivery costs one hundred.

Ocean freight only works at volume. A twenty-foot container holds 2,000-3,000 units. Anything smaller carries a disproportionately high unit cost.

Traditional model:

Direct fulfillment:

You test with ten percent of the capital and a fraction of the downside.

More tests lead to better data. Better data leads to better inventory decisions.

But if you manufacture in Asia and sell in North America, ask yourself:

Are you optimizing for the numbers on your invoice or the dynamics that actually shape your cost structure?

Zone premiums compound. 60-90 day cash cycles drain capital. Quality issues discovered weeks late become expensive write-offs. Container minimums push you into conservative product decisions.

These do not appear as line items. They appear as slower launches, higher inventory risk, and reduced agility.

Direct fulfillment is not simply cheaper or faster. It is a different operating model. The question is not which model looks better on paper. It is which model aligns with how you manufacture, test products, and recover cash.

2026 will reward brands that run leaner and make decisions faster. Safety stock becomes a liability when demand shifts quickly and capital remains expensive. The brands that win will be the ones that reduce the time between production and sale, shrink their cash conversion cycle, and close the gap between quality issues and correction.

Direct fulfillment makes these adjustments possible. You carry less inventory, react faster to demand, and recover cash sooner. If your 2026 planning includes increasing agility and reducing working capital pressure, your fulfillment model matters more than your warehouse location.