Revenue is up. Order volume is up. You have more data than ever. Yet your fulfillment setup feels more fragile, not less.

That is not founder anxiety. It is how decisions about inventory, timing, and partners interact once you move past scrappy early stage into a few million in annual revenue.

This post explains why that risk shows up, which choices are actually hard to undo, and what to consider before you talk to any logistics partner.

On paper, scale should make you feel safer. More cash in the bank, negotiate better rates, and have more predictable volume.

In reality, risk often feels higher.

Once your annual revenue hits the million dollar range, you sit in an awkward middle. Mistakes hurt your bottom line. You still lack deep buffers. And you start making structural decisions that do not quietly unwind.

The environment is not getting calmer either. With trade rules and tariffs shifting, the 2025 RSM US Supply Chain Special Report found that most mid-market supply chain leaders now prioritize technology, compliance, and outsourced services to stay aligned with new requirements, not just cost.

At a global level, the 2025 OECD Supply Chain Resilience Review shows how tightly connected modern supply chains have become. Many key industries rely on a small number of trade corridors, and true resilience requires agile, adaptable supply chains rather than simple reshoring.

When one bad logistics or inventory decision could wipe out a quarter of progress, that is a rational read of the system you operate in.

Not every fulfillment decision sits at the same level. Light decisions are things like tooling and minor terms. You switch an analytics tool, adjust an SLA, or renegotiate a surcharge. You pay some switching costs, but your business shape does not change.

Heavy decisions involve working capital and physical stock. Where you hold inventory, how much you commit to each region, and what lead times you build into planning.

These put real weight on your balance sheet. Once you treat these as capital allocation decisions, not just ops preferences, you start to see why they feel so risky as you grow.

McKinsey's 2025 article on optimizing working capital explains that focusing on working capital early can unlock meaningful liquidity. A lot of that improvement comes from how cash flows through purchasing, production, and inventory.

If you sign a new analytics tool and regret it, you cancel. If you move four months of stock into a region assuming demand will be there and you are wrong, you tie up cash in the wrong place. To fix that, you discount, move product at extra cost, or sit on dead stock while other parts of the business starve for cash.

Some fulfillment calls are capital allocation decisions that lock you in for 6 to 18 months.

Big brands misjudge demand too. The difference is absorption.

A global retailer spreads one bad inventory decision across hundreds of stores and multiple channels. They lean on markdown budgets, credit lines, and other product lines still working. The mistake hurts but gets diluted through scale.

For a growing ecommerce brand, the same mistake lands differently. A seasonal bet that does not move, a market expansion that lags, or a wholesale launch that slips shows up quickly in your cash, not just your P&L.

McKinsey's Supply Chain Risk Pulse 2025 points out that tariffs became the defining issue for global supply chains in 2025. In that survey, 82% of respondents said tariffs affect their supply chain and many reported that 20 to 40% of activity now feels that impact.

These are not small companies. They still scramble when policy, costs, or demand shift. Scale does not remove fulfillment risk. It changes who absorbs it and how survivable each error is.

Stage one: 300-500 orders a month into a new region

You manufacture in Asia and want to grow France. You have early traction but lumpy demand. You can hold inventory near the factory and ship cross-border, or move stock into a local French 3PL. The second option looks attractive but is risky if demand comes in slower. You tied cash up in a node that might not turn.

This is where Portless de-risks international expansion. You keep inventory upstream in our Shenzhen hub, ship cross-border as orders come in, and validate French demand without committing capital to local warehousing. In this stage, bias toward reversibility while you validate demand.

Stage two: 2,000-3,000 stable orders a month

Back to France. Now you have run campaigns, tested channels, and seen consistent demand across several cycles. Those early 300-500 monthly orders have grown into 2,000+ with predictable patterns. Moving inventory into a French 3PL starts to look rational. You still carry risk, but you are making a heavy decision with signal, amplifying something you have already proven through the upstream model. Heavy decisions make more sense once you have proven, repeatable demand.

Forecasts miss. New products over-perform or flop. Retail partners change timelines. What you control is how your network behaves when you are wrong.

You place stock closer to expected demand. When you are right, customers see faster delivery. When you are wrong, inventory sits and you pay storage in a node that does not move.

You hold stock in one or a few locations.

Traditional centralized inventory often sits in your target market. This feels efficient when demand aligns with your plan. But when shifts, you ship further and struggle to respond quickly.

The alternative is strategic centralization. Keep inventory upstream in a factory-adjacent hub, closer to supply than to demand. This changes your decisions. You are no longer committing today to how much sits in North American or European warehouses for three months. You keep stock near the source, then let actual orders determine where units go.

That is exactly how Portless operates. Our Shenzhen fulfillment center is hours from many factories in China. Inventory lands there first. Orders flow in from Shopify and other channels. Packages hand off to more than 20 last-mile carriers. Most brands see 6 to 9 day delivery to North America and Europe.

Learn more: Inside Portless Operations

The benefit is responsiveness. You hold inventory centrally but with better information about where demand actually is, not where you forecasted it would be months ago.

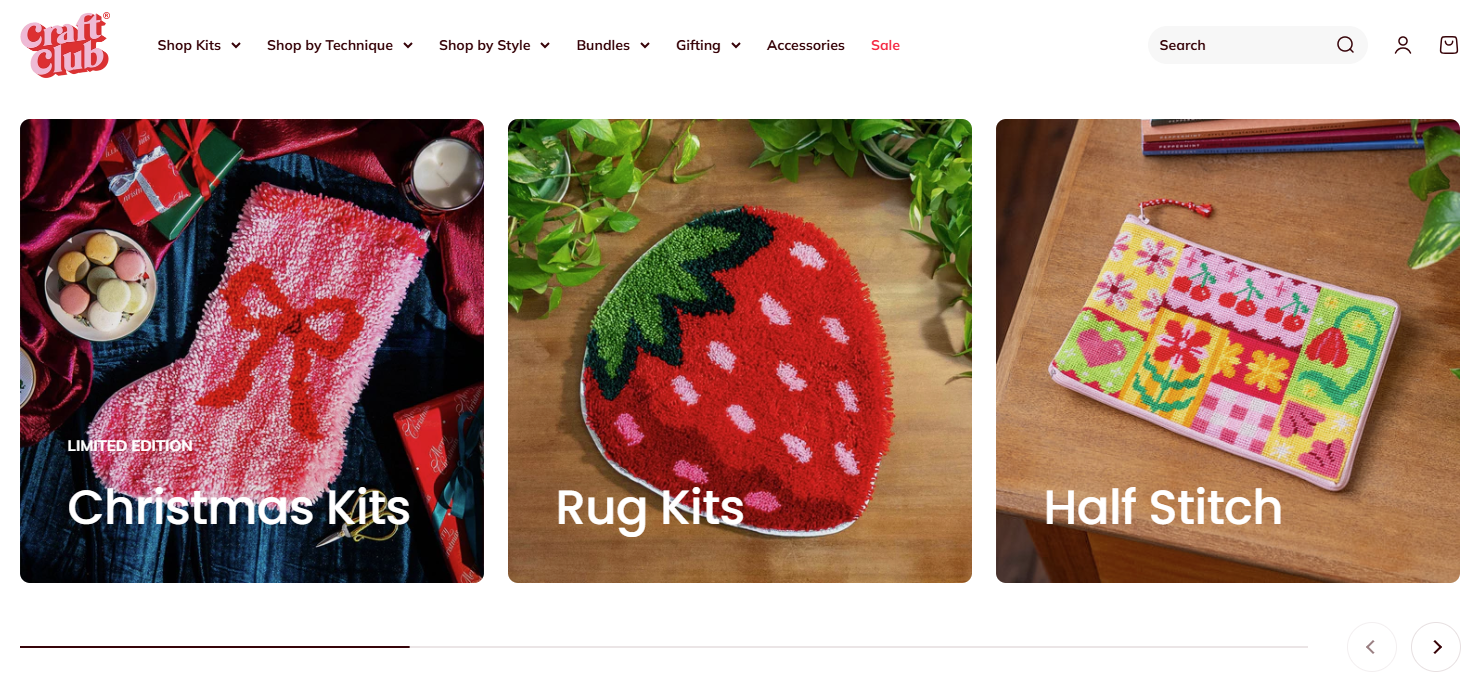

Craft Club had demand, but their traditional model turned inventory into a growth ceiling. Long lead times meant frequent stockouts or wrong stock in the wrong place.

After moving to Portless, here’s how their founder Nikos Maniaty described three changes:

When inventory could move from production into global shipping in days, the team stopped planning around container cycles and started planning around campaigns.

You will never remove risk from fulfillment. The goal is to understand which decisions deserve the most caution because they lock in your capital and options in ways that are hard to reverse. When you see those decisions clearly, fulfillment stops feeling like a threat and starts to look like a system you can design on purpose.

What is the biggest fulfillment risk for growing ecommerce brands?

Making heavy inventory decisions before you have repeatable demand data. These tie up working capital and are hard to reverse without markdowns or extra freight costs.

What is a delayed commitment fulfillment model?

A model that keeps inventory upstream near production and commits units to final regions only when orders arrive, so you pay duties and freight on units that already sold, instead of on large, speculative batches.

When should I use forward deployed inventory?

Use it when you have proven, repeatable demand (2,000+ stable monthly orders). Use centralized inventory when demand is uncertain.

How can I reduce my cash conversion cycle?

Keep inventory closer to production, use favorable payment terms with factories, and ship orders as they arrive rather than prepaying for large container shipments.